IB

Si dice che la fotografia congeli il tempo, per immobilizzare l'attimo dallo scorrere del tempo.

Così, entrando nel tuo studio a Roma e vedendo la tua serie sui vecchi macchinari Olivetti,"BIT" pinholes, sono subito stata colpita da un gran senso di connessione tra il passato e il presente. Stai esplorando nozioni di tempo e contesto storico o forse più specificamente è una ricerca del patrimonio artistico sociale all'interno del tuo stesso lavoro?

CN

Nella serie BIT, ho ritratto nature morte di tecnologie obsolete, stavo cercando di guardare il secolo passato la mortalità della tecnologia e come queste forme ricoperte di polvere fossero gia antiche come dei fossili.

La scelta della fotografia stenopeica, deriva in parte dal fatto che in se stessa implica una lunga contemplazione del soggetto e della sua registrazione.

Cerco la bellezza dello scorrere del tempo nei toni fotografici e nella patina delle superfici.

Come nel quadro La Muta (1506-1507) di Raffaello si percepisce miracolosamente il passare del tempo nella pittura, questa idea di durata ispira il mio lavoro.

IB

Nella performance 'La Resa' (2006), una documentazione di te stessa in vari ambienti, in pose quasi cinematografiche, con la tua bandiera di resa, stavi ancora una volta giocosamente ricontestualizzando un gesto simbolico del passato nei luoghi del tuo presente?

CN

Con l’idea di esorcizzare il concetto di “Resa” sono partita per delle escursioni solitarie. Con una bandiera bianca rudimentale. Mi ricordava il fazzoletto bianco con il quale i civili e i soldati si arrendono durante la guerra.

In questo caso ho usato l’autoscatto di una Leica.

Ho cercato di dare a questa serie di fotografie, l’idea ironica che riecheggia i fotogrammi di un materiale di repertorio immaginario.

Durante queste perlustrazioni, ho disperatamente cercato di far arrendere dei pezzi della mia terra al conflitto. Intimamente si è trasformato in un rito liberatorio.

IB

Potresti spiegare l'importanza del metodo tradizionale di fotografia stenopeica nel tuo lavoro?

CN

E’ paradossalmente un’idea filmica di intendere la fotografia, una serie di istanti sovrapposti il cui tracciato sarà l’immagine finale che viene catturata più che da un obbiettivo, da un occhio socchiuso e discreto, quasi umano.

La casualità dell’inquadratura, dovuta all’assenza di un mirino fa si che il soggetto viene inquadrato ad occhio nudo, questo per me rende lo scatto più fisico ed insieme perentorio.

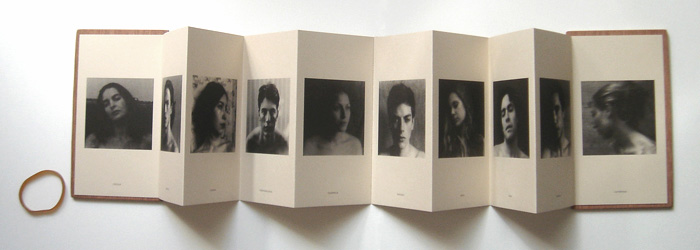

Nelle sedute con il soggetto si crea un unione nel momento intuitivo dello scatto, dopo il quale, in una apnea statuaria si impressiona la pellicola.

A volte le esposizioni durano più di un minuto. Durante queste lunghe pose, scopro le fisionomie psicologiche del soggetto.

Quello che cerco di ottenere soprattutto nei ritratti, è attraverso l’essenzialità dell’immagine, la nudità senza tempo.

IB

La luce sembra avere un ruolo così importante in tutto Il tuo lavoro, sia nell’ambientazione dei tuoi soggetti che nell'importanza della superficie pittorica in lavori come 'KosmoKid' e 'Euro-fun'. Potresti parlare del tuo lavorare sinonimamente come artista nei campi della pittura e della fotografia?

CN

Credo di avere intense ossessioni che si alternano. Tendo a non legarmi solamente ad un linguaggio, mi auguro piuttosto di trovare una poetica comune tra diverse forme espressive.

Questo non mi preoccupa. Anzi, amo la sensazione di perdermi per rinnovarmi nella paura di un nuovo confronto.

La mia pittura, automatica e tradizionale è una pittura ad olio, lavoro con questi colori sui quali la luce si posa meravigliosamente, restituisce una luminescenza simile a quella della pelle umana. Per questa serie di quadri, ho cercato nelle materie e nel ritmo di esplorare il gioco continuo tra superficie e luce. Ricordo altri due quadri di quella serie Wet backs e Half pint. Quando dipingo trovo confortante sprofondare nella solitudine, mentre con la fotografia sono più attenta allo spazio e a quello che gli ruota intorno. I ritratti, mi portano naturalmente a una commistione di sentimenti.

IB

Come hai incontrato i vari modelli per la tua serie di ritratti?

CN

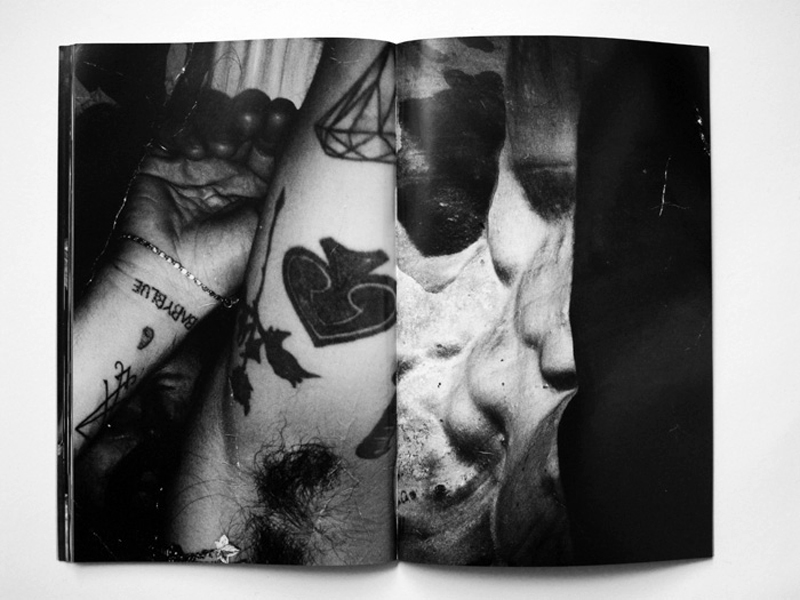

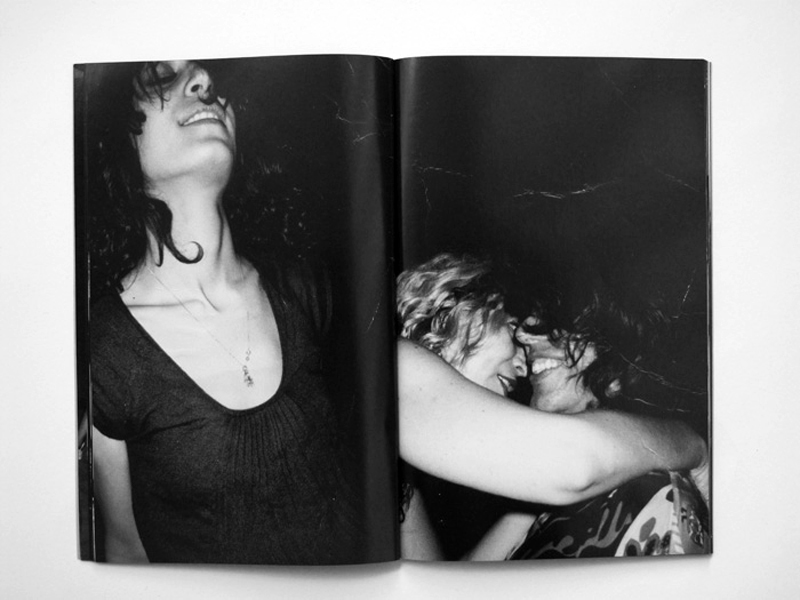

Pierfrancesco stava lavorando, andavo a bere del vino e l’ho incontrato. Ho subito istintivamente pensato di ritrarlo. E’ stato il primo, non ancora a studio ma in una vecchia carrozzeria convertita in galleria, piena di zanzare. Mi sconvolse come riuscì subito a scivolare nello stato di abbandono che questo lavoro ci richiede. Nina era ad una festa sulla terrazza di un palazzo romano. non sapevo della sua esistenza di amazzone bambina. Vederla mi ha trasportato in una fantasia ad occhi aperti, storie immaginarie tra i singoli ritratti. Di desiderio e gioco tra gli stessi personaggi. Cecile, è da sempre vicina, volevo ritrarla nell’intimità del suo pensiero. La giovane sposa. Al piano di sotto del mio studio Francesca impara a fotografare come una sfinge serafica anche accogliente. Michele non lo avrei mai immaginato come mi è apparso quel pomeriggio, un aristocratico Boemo. Brando non va a scuola per andare a vedere i Caravaggio e venire nel mio studio a farsi fotografare. Mi incanta la sua giovane ambiguità, lui si fa portare. Molti amici artisti qui a Roma vorrebbero ritrarre Chiara. John, è uno di questi. Giorgio l’ho visto che fotografava gli amici mentre bevevano e chiacchiravano sotto gli alti pini. Stare fermo per lui è difficile e sbatte conto gli angoli. Da qui Still Stories.

IB

E' interessante che tutti i tuoi soggetti siano amici o persone di cui avevi sentito parlare, perché quando vidi i tuoi lavori per la prima volta mi è subito venuta in mente la fotografa di società Vittoriana, Julia Margaret Cameron.

Negli ultimi 12 anni della sua vita la Cameron diventò uno dei più importanti fotografi amatoriali del tardo ottocento in Gran Bretagna. Scattava fotografie incredibilmente intense di amici e di bambini, utilizzando una varietà di lunghi tempi di esposizione, sfuocando intenzionalmente per potenziare l'intimità dello scatto. La sua triste storia la vede classificata come il brutto anatroccolo della famiglia, e così si dice che la Cameron si sforzasse per catturare la bellezza nel suo lavoro.

"Ambivo a catturare tutta la bellezza che mi passava davanti e finalmente quest’ambizione è stata soddisfatto". Questa è una mia osservazione e un mio paragone -sicuramente ci sono altre figure storiche o contemporanee che importanti per te?

CN

Mi sono avvicinata a questa fotografia in modo sperimentale, incuriosita dalla scoperta della camera oscura e dei suoi risultati. Solo in un secondo tempo, mi sono piu attentamente documentata sugli albori della fotografia.

Come nel caso della raccolta della Gorge Eastman House Collection.

Nello straordinario lavoro di Julia Margareth Cameron che tu mi hai fatto conoscere, trovo sconvolgente nel paragone con le immagini contemporanee, la profonda mancanza di consapevolezza del fotografato rispetto al mistero della nuova invenzione.

Persino nella foto di reportage, si percepisce un intensità lontana dalla nostra sensibilità.

Come nel caso della stampa ad albume di Alexander Gardner che ritrae Lewis Payne uno dei cospiratori dell’assasinio del presidente Lincon prima della sua esecuzione,(1865). Ai nostri occhi non c’è frattura fra documento e elaborazione poetica, fra messa in scena e naturalezza, proprio perchè fotografo e modello stanno creando insieme nello stupore della nuova invenzione.

E di nuovo penso al mistero dello scorrere del tempo nell’opera. Come Questa sensazione si avverta così più profondamente nel passato e oggi, in un artista come Hiroshi Sugimoto vedi la serie marina.

IB

La prossimità del modello in tutti i tuoi ritratti è molto seducente, in particolare il loro sguardo sconcertante e la loro impressionante presenza fisica.

E' stato difficile raggiungere questo risultato?

CN

Uno sguardo atemporale… forse il risultato della stanchezza dovuta alle mie lunghe pose, comunque un varco oltre il proprio narciso dove affiora qualcosa di più segreto e sorprendente per loro stessi. Questo abbandono con lo scorrere della pellicola diviene sempre più evidente. E’ qualcosa che affiora naturalmente e credo che abbia a che fare con il loro piacere.

IB

Mi domando però la ragione perché tutti i modelli Maschi sembrano rapportarsi alla macchina fotografica frontalmente, recitando ciò che la teorica cinematografica Laura Mulvey classificherebbe come lo sguardo attivo o maschile - mentre le femmine in posa adempiono il ruolo passivo spostando lo sguardo dall'obbiettivo.

E' stata una scelta voluta?

CN

Non posso dire questo sia intenzionale, è il gioco della seduzione. Penso che in Italia si usi lo sguardo e si usi abbassare lo sguardo, non come segno di sottomissione bensì come ancora un'altra forma di seduzione. E’ tradizione guardare.

Credo che nei soggetti maschili più che aggressività ci sia un sentimento di desiderio e insieme di identità.

Muovo i modelli in un totale sonnambulismo, non ho la percezione esatta dell’inquadratura e loro come statue di loro stessi si rappresentano. Cerco di percepire l’intensità di quello che scorre nelle loro menti..

IB

Hai scelto un formato di dimensioni domestiche per queste stampe

per aumentare l'intimità dei soggetti?

CN

Si, per questa serie di ritratti, il formato è appena più piccolo dell’ 1:1, una suggestione che ho avuto nel guardare i ritratti di Antonello da Messina come nei fiamminghi, dalla clavicola in su direi.. L’idea di intimità che tu cogli è una decisione conscia di trasmettere un senso di affettività a chi guarda.

IB

Ci sono chiari segni che i lavori rientrino in una

tradizione storica di stampe montate a secco su pannelli, ma sembra che le opere non siano state incorniciate, c'è

una ragione per questa scelta?

CN

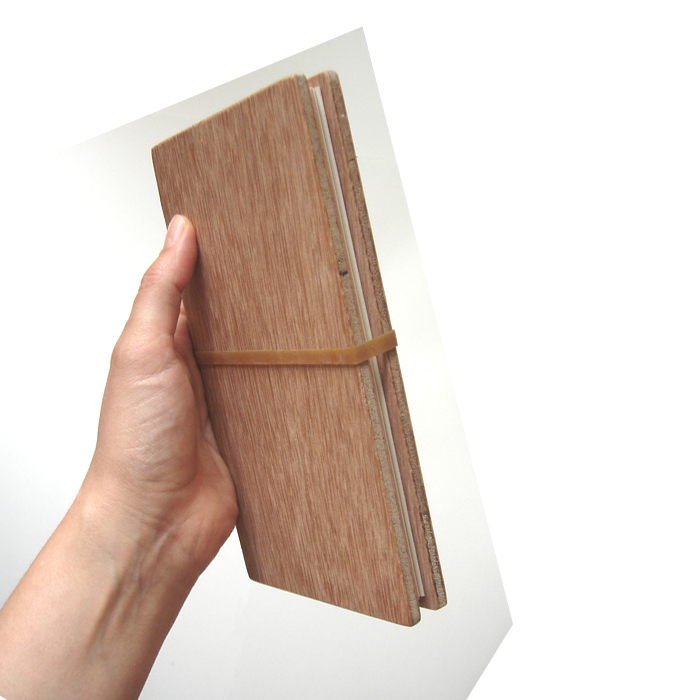

Per questa serie ho fatto costruire delle cornici-cassette di legno di noce nazionale grezzo. Un’ idea di storia naturale applicata alle mie storie immaginarie.

Cassette museali per meteoriti e farfalle.